I didn’t know there was a name for it. But when I started reading about metamodernism, it gave me a new tool to describe something I had deeply internalized to the point that it had faded into the background.

The broader applications of metamodernism inspired me to write this. But this annotated playlist could not possibly attempt to spell out the full scope of change which could come about in a metamodern era. Rather, in the spirit of this way of feeling/seeing/being, this is a lighthearted introduction to something very serious. My intention today is simply to introduce you to metamodernism through my own musical interpretation. In this way, I hope it will be more resonant and easily embodied in real life, where I see it having a profound impact on you, your relationships, and the world we share.

“Metamodernism, as we see, it is not a philosophy. In the same vein, it is not a movement, a programme, an aesthetic register, a visual strategy, or a literary technique or trope… For us, it is a structure of feeling.” - Timotheus Vermeulen & Robin van den Akker

Learning about this subject has helped me reflect on my personal development (and deficits) and how I can be a positive force in the lives of all — people, animals, and planet. I grew up surrounded by left-leaning memetic tribes, and felt sure about the importance of having a society with a strong social foundation. I was drawn to the scientific worldview and the so-called “grand narratives” of modernism. And I was also aware of postmodernism’s deconstruction of these along with objectivity, history, and progress. But I never felt settled in one or the other — both seemed incomplete. Modernism was too bull-headed, and postmodernism too indiscriminately destructive. Vermeulen and van den Akker write:

“Indeed, if, simplistically put, the modern outlook vis-à-vis idealism and ideals could be characterized as fanatic and/or naive, and the postmodern mindset as apathetic and/or skeptic, the current generation's attitude — for it is, and very much so, an attitude tied to a generation — can be conceived of as a kind of informed naivety, a pragmatic idealism.”

And Hanzi Freinacht adds:

“Each of them is a kind of underlying structure of the symbolic universes that constitute our lived and shared realities. So each one of them roughly have an ontology (theory of reality and what is ‘really real’), an ideology (‘theory of what is right and good’) and an identity, an idea of who or what the self is.”

When I read books like “Sapiens”, it drove home the importance of storytelling and religious mythology in human society. Our civilization simply wouldn’t have evolved without certain memes, but this comes paired with cautionary tales. The conclusion, in my view, is that we need new stories. We need metamodern stories, or metanarratives, which recognize their own value, limitations, and dangers. I do not think we should give up on storytelling, but I am not hoping to nurture a new generation of dogma, either.

This is why metamodernism’s quality of oscillation seems so natural to me. The space between -isms turns into a liminal home. And in this in-betweenness, I see a way beyond — a path partially illuminated by the modern and postmodern and the emergent properties of a newly-formed whole. I believe this way of feeling has the potential to shift the way we see the world and place us in a revolutionary trajectory. It’s the view that allows us to be protopian instead of childishly utopian or nihilistically dystopian, and to “pursue a horizon that is forever receding.”

“Metamodernism is variously called a cultural paradigm, a cultural philosophy, a structure of feeling, and a system of logic. All these phrases really mean is that, like its predecessor’s modernism and postmodernism, metamodernism is a particular lens for thinking about the self, language, culture, and meaning — really, about everything.”

- Seth Abramson

And, throughout, I provide links and quotes to some wonderful blog posts, papers, and books for those who want a deeper dive into this subject.

I encourage you to listen to the playlist on Spotify before (or while) you read on. It contains additional songs other than those listed below, which I leave open to your own interpretation.

Time: The Donut of the Heart, by J Dilla

The song is short, instrumental, and written from the artist’s hospital bed. J Dilla died from Lupus just three days after the album’s release. This song in particular exemplifies J Dilla’s metamodernism. To my ears, it is not strictly either happy or sad. It evokes both, and something else unknown. Life is an orderly mess, and so is this song.

“There is no reason to not relate to reality as viewed both from a sense of blissful clarity and as dark, screaming confusion. All of this is part of reality.” - Hanzi Freinacht

“Time: The Donut of the Heart” makes my heart stop. It’s a beautiful tangle of yearning, sorrow, hope, love, sex, joy, and death. Was Dilla’s final creation an act of terror management, or of self-transcendence? For artists before him like Warren Zevon, musical creation seemed inexorably linked to the realization that death was approaching sooner than expected.

These artists and others could perhaps have been individualistically warding off death by doing what made them feel most alive. But maybe they were selflessly transcending that part of themselves which could not live on by letting us hear some fragment of their souls. And if “soul” doesn’t sound sufficiently metamodern, feel free to reinterpret it as “Integrated Information” or “Strange Loop” or something else “in pursuit of a plurality of disparate and elusive horizons.”

As Zevon wrote in his swan song, “Keep Me in Your Heart”:

“Shadows are fallin’ and I’m runnin’ out of breath

Keep me in your heart for a while

If I leave you it doesn’t mean I love you any less

Keep me in your heart for a while”

Should we feel joy that we get to experience the music of people like Warren Zevon and J Dilla, or should we empathically feel grief and anger and fear – the emotional substrate from which art often grows? Perhaps the answer is: Yes.

D.R.E.A.M., by Pharoahe Monch and Talib Kweli

An acronymic song within an acronymic album (“PTSD”) which pays homage to hip-hop classic, “C.R.E.A.M.” by Wu-Tang Clan is nothing if not meta. What makes this song particularly metamodern, however, is its embrace of both post-traumatic stress and post-traumatic growth.

“But to truly accept the pain of life and deal with it, we require a lot of comfort, support, security, meaning and happiness. This is also what the ‘posttraumatic growth’ researchers claim, i.e. the folks who look into how people gain positive, life-changing insights in the wake of personal crises.” - Hanzi Freinacht

Pharoahe Monch has said the album “came out of the depths of a period of depression”, but that his goal in music is always “pushing the culture forward”. D.R.E.A.M. traverses a spectrum of potentially conflicting, potentially complementary emotions. And the title of the song is unpacked by Monch at different moments to mean both “Destiny Rules Everything Around Me” and “Determination Runs Every Aspect Mentally”. Are forces of control internal, external, or in metaxy between opposing poles?

The artist I hear in this song is demonstrating what Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker meant when they wrote that metamodernism is:

“A constant repositioning between attitudes and mindsets that are evocative of the modern and of the postmodern but are ultimately suggestive of another sensibility that is neither of them; one that negotiates between a yearning for universal truths and relativism, between a desire for sense and a doubt about the sense of it all, between hope and melancholy, sincerity and irony, knowingness and naivety, construction and deconstruction.”

Metamodernism seems incompatible with being stationary, physically or emotionally. A song like “D.R.E.A.M.” could not be written in the absence of pain any more than it could without hope. We should not expect that Pharoahe Monch is either depressed or not — but also not that he is wildly oscillating between extremes. And the song, in that way, invites us to take on a metamodern outlook – what I see as the integration of both the default optimism, joy, and openness of childhood, and the murky but useful shadow of adulthood. This can be seen as part of the metamodern aesthetic of simultaneity, which Seth Abramson thinks is a better view of what had so far been thought of as oscillation:

“Early descriptions of metamodernism suggested that an individual thinking metamodernistically “oscillates” between opposing states of thought, feeling, and being — almost as though human beings were pendulums swinging between very different subjectivities. More recent understandings of metamodernism emphasize, instead, simultaneity — the idea that the metamodern self does not move between differing positions but in fact inhabits all of them at once.”

I came across other objections of oscillation:

“If oscillation is failed synthesis, then we should stop oscillating. Rather than trying to bounce across multiple perspectives, we should be creating new perspectives by actively grappling with and resolving the tensions between existing ones.”

But in relation to synthesis and simultaneity — I’m convinced that each is still useful. I see it as one face of a more universal principle of exploration-exploitation.

We should exploit a useful synthesis if it can serve the common good, but understand that, as an alloy, it is no longer its base metals, and that something was inherently lost in the process. As Zak Stein wrote:

“The metamodernist has her own unapologetically held grand narrative, synthesizing her available understanding. But it is held lightly, as one recognizes that it is always partly fictional — a protosynthesis.”

In metamodernist terms, I would say that oscillation and simultaneity are types of exploration of the unknown and paradoxical, while synthesis (or protosynthesis) is exploitation of our best-available information. I suspect that, going forward, metamodernists will make us feel uncomfortable with their syntheses and truth-claims. But it will be an expression of a cultural turn towards sincerity, hope, love, and earnest enthusiasm.

Furry Walls, by Infant Sorrow

Russell Brand plays a semi-fictional version of himself in a pair of films, “Forgetting Sarah Marshall” and “Get Him to the Greek”. And in this universe, he is rock god Aldous Snow from a band called Infant Sorrow. Brand has been noted before for his metamodernist tendencies. I think this song captures it perfectly.

In Get Him to the Greek, Aldous Snow has hit hard times after a massive musical failure. His critically panned song, “African Child (Trapped in Me)”, was arguably a well-meaning attempt at a political call-to-action. But the song is so bad it oscillates between tragedy and comedy. Excerpted below:

“I have crossed the mystic desert

To snap pictures of the poor

I've invited them to brunch

Let them crash out on my floor

…All these blowjobs in limousines

What do they matters

What do they mean

To the little African child

Trapped in me”

Infant Sorrow had previously made it big with hit songs like “The Clap”, but now seemed unsatisfied with music that lacked meaning and depth. So naturally, he wrote the song quoted above.

It was only after these ups and downs, and all the self-reflection you can pack into a 109-minute buddy-comedy, that the fictional musician released “Furry Walls”. In a way, this could be seen as resigning or selling-out. Giving up on the African child trapped in him, and getting rich off of catchy but vapid pop music.

I prefer to see it as metamodernism’s characteristic of being between and beyond that from which it draws. Infant Sorrow’s The Clap was catchy, but didn’t attempt to be meaningful, like African Child. And the latter made a beeline for meaning at the expense of being catchy. Whereas Furry Walls seems more self-aware of what it is and isn’t. Maybe it won’t change the world, but it does bring joy to countless people. Meaningfulness becomes the second-order effect of catchiness. And, in this way, a song with a metamodern “informed naïvety” is greater than the sum of its parts.

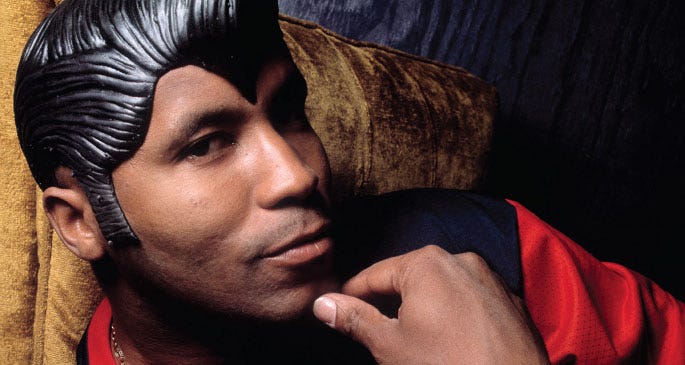

Livin’ Astro, by Kool Keith

The song opens with the declaration:

“Every morning I wake up, lookin’ in the mirror

I am the original Black Elvis”

You would think that a Black Elvis-themed concept album would be the strangest part of Kool Keith’s musical journey, but the fanatically prolific artist has released 38 albums since 1988, and this is just one star in the constellation. He really ventured out to the edge of hip-hop’s Hubble sphere with his horrorcore and pornocore.

It’s for these reasons he stands out — having a career which started in the golden age of hip-hop, and yet almost immediately began “exploding the serenity of the moment”, á la Russell Brand. Hip-hop was (and is) more than oscillation between east coast and west coast. But I have a special respect for Kool Keith’s music, which somehow shattered the conventions of hip-hop without the cynicism or detachment of postmodernism. He made music that was absurd and yet sincere.

“To ‘be a metamodernist’ is to apply oneself to sincerity with religious fervor, while keeping an ironic smile at one’s own self-importance.” - Hanzi Freinacht

“That is to say, metamodern irony is intrinsically bound to desire, whereas postmodern irony is inherently tied to apathy.” - Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker

His music was not disrespectful or dismissive of the shoulders he and all artists stand on. With Kool Keith, I hear an artist yearning for the future, but propelled by an earnest love of the past and present. Hybrid irony-earnestness is a telltale sign of metamodernism — enough so that we may need a shorthand, like “ironesty”.

Shadows Crawl, by Torii Wolf, Rapsody & DJ Premier

I was checking out this list of metamodern films and TV shows and noticed a common theme of mixing dreams and waking life. The dreams seep into reality — they are more real than real, and reality becomes stranger than fiction. I wanted to capture that in my metamodern playlist, and remembered this collaboration called “Shadows Crawl”. A few lines stand out:

“I fell asleep on my lover, had a dream about another

…

My dream lover got my real man mad as whoop!” - Rapsody

And:

“I'm talking in my sleep

Where my shadows crawl out of me“ - Torii Wolf

I believe there is a common metamodern motivation for appreciating both stories and dreams, for synthesizing multiple religious, spiritual, and scientific perspectives. Simply, neither dreams, stories, or reality stay sequestered. They are co-creative realities, not fiction and non-fiction.

“When enacting these meetings of the secular, the contemporary spiritual, and the ancient, I noticed that the performance of these combined worldviews is engaged in a manner that neither reduces nor essentializes, nor pits them against one another, nor asserts the supremacy of any one, but rather, accounts for all of them.”

- Linda Ceriello

I came across literary tools like “faction” (blending of fact of fiction), “theory-fiction” (blending of scholarly theory and fictional narratives), “autofiction” (blending of autobiography and fiction), and “magical realism” (blending of magical or supernatural elements within otherwise highly-realistic stories).

These are broadly attributed to postmodernism, which highlights the way in which these styles call truth and objectivity into doubt. And, in turn, I believe a metamodernist will embrace postmodernism’s braided fictional-factual realities, but repurposed in our time as a method of reconstruction.

“In the early 2000s, a scholar from New Zealand, Alexandra Dumitrescu, analogized metamodernism to ‘a boat being built or repaired as it sails,’ and it’s precisely this sort of reconstruction that metamodernism permits — a manner of construction in which we simultaneously acknowledge that things are still in pieces, but also that the pieces we have must be treated as useable even if we still have some doubts about that. A metamodern ‘reconstruction’ is not merely a ‘construction’ because it recognizes that we are trying to ‘repair’ something that was previously deconstructed; and it’s not a deconstruction because we are, however cautiously and skeptically, setting about trying to build a ‘whole’ object.”

- Seth Abramson

We orient ourselves towards the building of grand narratives and a common understanding of truth. But these do not cancel out stories and dreams. A metamodernist is a pragmatic storyteller who knows that this is an inherently manipulative act which can only sometimes be justified. We carefully wield the power of storytelling, mythology, religious perspectives, and blending of fact and fiction. But metamodernism doesn’t seek dupes or followers or even students. I think it seeks, and can only function through, co-creators of ever-greater understanding.

The Myth, by Mithril Oreder

I’m sorry it took so long to get to the six-minute-long blockchain posse cut — to make it up to you, here’s a bonus thirteen-minute blockchain posse cut.

This song is an example of “The Epic”:

“…a rebellion against postmodernism’s tendency to cast shame on ebullient, unabashed self expression. I’m talking about extravagant performances, lush musical arrangements, cautionless embrace of technology, over-the-top sexuality, excesses that don’t stop at just being provocative, but engage grandiose, hero-filled storytelling.”

And I find that, yet again, we see a melding of art and life in this song. With the likes of Dogecoin confusing the general public about the revolutionary nature of blockchain (which, for brevity, I unabashedly rank alongside computers, the internet, and artificial intelligence in its importance), you would be forgiven for thinking that the “Mithril Ore” being rapped about in this song is fictional.

In fact, this blockchain anthem, which you likely streamed on Spotify, is subtly telling you about a radical alternative to this very service:

“Mithril Ore… serves to decentralize MUSIC PUBLISHING AND MUSIC STREAMING ROYALTIES…

Mithril Ore token aims to unite fans/artists/music publishing/ and music streaming royalties with MORE token.”

I believe there is more than a superficial connection between metamodernism and blockchain, which is something I will no doubt write more about at a later time. But for now I’ll just tease this connection, while letting The Myth stand on its own as a representation of The Epic.

But this is a metamodern theme with many faces, and I believe that if indeed “over-the-top sexuality” falls within it, further discussion is warranted — which, again, will need to be carried on in future writing. But generally The Epic, as it pertains to sexuality, makes me think of songs like “Facefuk” and “Bling Bling”.

The overly-simply view is that this is a strictly positive trend towards greater agency for women and liberation from patriarchy. I think that part of it is great. But it was hard for me to capture my full range of thoughts through the aesthetic of either of the songs above. Something tells me that we are only in the middle of the story, and that un-tabooing sexuality and challenging power dynamics, especially for women, is a necessary step but not the end of the road. Zak Stein writes:

“The overt repression of sexuality has been the traditional conservative root of emotional dysfunction, and while Western cultures have overcome much of this overt repression, the result has been a different kind of erotic truncation. Where sex is not repressed it is hypertrophied; instead of a culture arranged to avoid sex, the culture is arranged to focus directly on sex.”

My contention is not that these songs are bad for us or bad for women. Like Stein, my hope is that we can “include but transcend” this progression, and that we recognize the ways in which our current culture limits (or “murders”) Eros:

“What humans experience as love and sexual desire are but facets of Eros… the force that drives reality itself towards greater contact and larger wholes.”

“The murder of Eros is always disguised. For example, limiting erotic energy to the merely sexual is a kind of erotic truncation, and perhaps the most common in our culture. An apparently liberated hook-up culture in which the mere act of sex is the most intimate thing shared between people distorts Eros in a different way than a traditional culture that would limit all sex to the marriage bed (with the lights off). But note that both truncate the erotic itself into the constraints of genital sexuality.”

What I hope you take away from this, even if it needs more space than this to explore, is that metamodernism is a way of understanding love, sex and intimacy as both deeply personal, and self-transcending. I see similarities to Arthur Koestler’s Janus-facing universe of “holons”, which each have a self-asserting and self-transcending tendency. And these forces create a dynamic balance. I believe metamodern lovers are sexually liberated, but not in a pathologically individualistic way. And similarly do not lose their individual wholeness in the process of self-transcendence.

“Or, more appropriately, one might say that it is ‘both and something else entirely, i.e. something the likes of which we haven’t encountered before.’ This is why metamodern reconstructions are often referred to as ‘both/and’ constructions (as opposed to the ‘either/or’ of much postmodernism or even the ‘both/neither’ of early conceptions of metamodernism). The hope is that ‘both/and’ constructions allow us to move ‘between’ the poles postmodernism has erected for us, and eventually ‘beyond’ the very spectra on which those poles reside.” - Seth Abramson

Perhaps super-sexuality is just the current incarnation of The Epic, and metamodernism will have to reinvent itself through both/and thinking, in ways that answers Zak Stein’s question:

“Can we place our individual love stories within the larger love story of the universe itself?”

Let’s hope so. Here’s to an erotic life.

Shoot Me in the Head, by R.A. the Rugged Man

I end the playlist with political metamodernism. If this were as easy to characterize as, say, the official platform of a political party, I could hyperlink and be done with it. In one sense, the musical aesthetic of this playlist is meant to help give you an intuition of the subject’s interplay with politics. Moreover, I think the place to write about it as it pertains to things like political and economic systems is in my future blog posts and upcoming book. I also want to leave metamodernism open as descriptive way of feeling and understanding the world, from which people can reach wildly different political conclusions. But a few things stand out to me as general themes in the intersection of metamodernism and politics.

First, the metamodern political mode is more “beyond” than “between” present ideologies. Instead of seeing a political spectrum, and finding ourselves stuck in the middle at the “Third Way”, metamodernism sees multiple 2D, orthogonal points of view, and seeks 3D, paradox-resolving alternatives. As Daniel Schmachtenberger writes:

“The 2D view of the cylinder is a circle from one perspective and a rectangle from another. Both are true “slices” of the reality of the cylinder; neither alone give a clear sense of the higher dimensional shape’s reality.”

“The key insight is recognizing these differing perspectives as orthogonal to each other rather than opposite ends of a gradient spectrum.”

“The recognition of orthogonality…gives us the cylinder, recognizes both lower dimensional perspectives as 100% true from their limited vantage point, and forces the recognition that a congruent picture is possible but requires a fundamentally more complex kind of perspective.”

Second, it is “process oriented”, as Hanzi Freinacht writes about Danish political party, “The Alternative”:

“Instead of being based on a readymade political program, the party was formed around a set of principles and values for how to conduct good political discourse and dialogue. The party also has political content, of course, a program with things they want to change, but this was subsequently crowd sourced by its members after the party got founded. Most central to the party’s founding and organization is still the how, rather than the what.”

Which could also be found in the distinction between a political “town hall” in which a politician answers voters’ questions, and an “Ephemeral Group Process” in which the goal is to cooperatively arrive at better and better questions. The focus is on the “metapolitical”, as Zak Stein writes:

“The metamodern approach begins in the realms of the metapolitical and only later comes back to consider the next best steps to take in terms of ‘politics.’”

And third, the songs I’m calling politically metamodern in this playlist share an over-the-top, exasperated disdain for the status quo, which tends to manifest as political “homelessness”:

“The Republicans ain't shit, the Democrats ain't shit

What would make you think that either side is ever gonna change shit?”

“Who I'm rollin' with? Nobody nobody nobody nobody

Who I know? Nobody nobody nobody nobody

Who I care about? Nobody nobody nobody nobody

Who give a fuck about me? Nobody nobody nobody nobody”- R.A the Rugged Man

Also seen through another song on this playlist:

“I just might vote for Donald Trump just cause it's legal (Ay, Dios mío)”

- Freaky

And performed naïvety and goonish behavior:

“I'm like ‘Cunt, pussy, slut, lick twat, lick dick’

No, my vocabulary ain't improved one bit

I'm the lowest of the lowest life-forms

And I make it painfully obvious every time I write songs”

This, to me, is the artist embodying, not endorsing, stagnation. R.A. the Rugged Man is not “the change he wishes to see” — he is creating a persona for the problem itself, so that it can speak to us directly. Another example is Pharoahe Monch, who, instead of writing as a man thinking about gun violence in his country, wrote a three-part series of songs in which he takes on the perspective of a bullet. I find that metamodern artists are often not performing as their actual selves. They pretend to be old-school misogynists and racists, or the 1%.

I see this as a metamodern mode of engaging with what we wish to change. A kind of oscillation or simultaneity of viewpoints. It says that we are not afraid of inhabiting any kind of perspective if it’s in service of creating a better world.

I found other discussions online about songs from the perspective of inanimate objects, and I do not think this aesthetic by itself is necessarily metamodern. Though Greg Dember does note that anthropomorphizing is one way that metamodernism can be expressed:

“The projection of human personality onto non-human creatures or inanimate objects can be seen as metamodern in that it is an unabashed, unapologetic showcasing of inner, felt experience. In effect, the author/work/reader is filled up with felt experience to the point where it spills over and imbues itself in non-human entities… inanimate objects being given consideration for their ‘feelings.’”

The distinction which I wish to point out is what I’ve noticed about the underlying intention. Maybe a song from the perspective of light is interesting and unusual, but my claim is that metamodernism uses “personas” and anthropomorphizing which contain a broadly understood (at the time) cultural critique. And, importantly, that the act of metamodern anthropomorphizing is self-obsoleting. By this I mean that it will remain fun to take on the perspective of a table from time to time, but taking on the perspective of a bullet is meant to be generative of societal change — ultimately (hopefully) making it less salient to take on the bullet-point-of-view. Writing such a song is an expression of the metamodern artist’s tendency to “be the problem you wish to fix”.

Outro

My goodness — this post is so long, we entered the post-metamodern era while you were reading. Everything you read is now obsolete, and you will have to come back for my next piece: A Post-metamodernist Playlist.

Alright, sincerely: I believe that if you’ve read this far, and had not previously encountered metamodernism, you now possess a rare and powerful artifact forged in the crucible of a global metacrisis. You must use it wisely. It’s been sharpened on both sides and also on another side we didn’t even know existed.

“Almost all political ideas have led to atrocities. As I write this down, I can almost feel the mutilation of innocents going on in closed prisons, somehow non-linearly emanating from my fingertips.” - Hanzi Freinacht

This playlist and my commentary was an attempt to capture my own journey into this field of thought, and to give you the tools you will need to understand and participate in this new cultural phase. Before you read this, it is highly likely that you’ve already encountered metamodern media — from Community to The Walking Dead to Rick and Morty. All of these artistic expressions are scouting ahead of our present reality, and give us a sense of what the future may hold. As such, I see metamodernism as a way to connect across impossible divides, engage in non-delusional hope, and move beyond what we currently see as possible — whether that’s global action on the climate crisis, new forms of government and economic systems, or a new love story.

“Theorists describe this way of thinking as an ‘as if’ philosophical mode; that is, the metamodernist chooses to live ‘as if’ positive change is possible even when we are daily given reminders that human culture is in fact in a state of disarray and likely even decline.” - Seth Abramson

As we write this story together, I hope you understand my “as if” mode as my way of contributing to the kinds of positive change which you may see as either impossible or resting upon other prerequisite changes. It’s one of the aspects of the metamodernist way of seeing the world that I didn’t know I was doing until people pointed it out to me and I subsequently found a name for it. I can see why it bothers people, so I want to state a few things that “as if” is not:

Magical thinking, utopianism, or uninformed naïvety, all of which act as if the impossible is possible. “As if” thinking can be taken only so far before reaching one of the labels above.

Glossing over the pain in the world, or the issues you see as most urgent. A proper application of “as if” in this context would be writing about radical changes in educational/academic paradigms and institutions. Someone focusing on this, you might think, is showing that they are ignoring the more pressing issues like the fact that 1 out of every 30 kids in US schools is homeless, or that housing and schools are still highly segregated. But I see the metamodern “as if” mode as including but transcending current struggles. We step temporarily into an imagined future, and act as if we are already in the world where we can dare to dream even bigger. This is where it can become excessive and be accused of utopianism or just plain insensitivity. But my view is that it can be a compassionate and ambitious addition to what I might call an “if this” mode — as in “if this happens first, then we can talk about that".

A way of shutting down a conversation or asserting that this is The One True Mode. Going along with the previous point, I think someone like myself who is comfortable in the “as if” mode needs to be equally ready to engage in different modes and from different perspectives. A metamodernist who voices this perspective is trying to enrich, not negate, other perspectives, and must be ready to oscillate and synthesize.

This is all to say, I’m only writing because I do not think our situation is hopeless, and I do not want you to be consumed by dread of a dead planet. I regularly feel a sense of joy when I think about the future — not because I know it will be awesome, but because I know it is in our power to make it so. Somberly, I’m not sure humans will even survive another century. But I’m not sure we’re doomed, either. And I believe we need to promise each other that we will still act as if we can make our world better than ever before.